I know what you’re thinking…

“Interesting Iron guy, you are officially off your rocker. Sanity has left the chat. The ether from all those prostock warmups finally got to you.”

(And you might be right. The prostock class at the NTPA Grand National hook in Farley last weekend was huge. I sniffed a lot of ether.)

But there’s a good reason for the title of this week’s Interesting Iron. Keep reading, and I’ll explain.

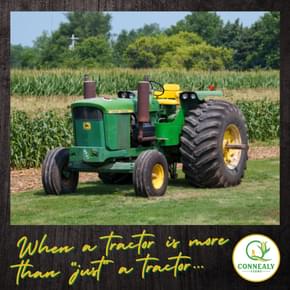

Sunsetting the SoundGard.

Y’know, there are tons of die-hard Deere fanatics who swear that SoundGards were the best things to ever roll out of Waterloo. At the end of the day, they might have a leg to stand on, too. Still, even as good as they were, they did have limits.

As horsepower increased, so did the size of implements. The SoundGard tractors made plenty of power; there was a model in the lineup that could handle just about any task. However, bigger and heavier implements lead to increased stress on castings. Mother Deere’s engineering teams could see the writing on the wall though; what worked now wouldn’t work in the future.

The problem is that for years, Deere used a stressed member frame design. It’s a good way to keep weight down a little, but the downside is that the engine becomes part of the frame. It’s subject to all of the same vibrations and load stress that the other parts of the frame are. There’s no way to really suspend it or take that stress away.

So, in 1979, Mother Deere’s engineers in Waterloo started looking at options for a more traditional body-on-frame design, like you might find underneath a truck. That study would eventually pave the way for a completely new, clean-sheet design that forever changed the way that tractors are built.

The M-Tractor.

At some point in 1984, a few years after the study had wrapped up, the top brass in Moline got on board to see what the future might look like with a main frame. Engineers from the States teamed up with engineers from Deere’s German operation in Mannheim to figure out the real nuts and bolts of how this new series of tractor would come together. Ultimately, the project was called the M-Tractor, and it would go on to become the 6000 and 7000-series.

The M-Tractor had one goal – increased efficiency. Nearly every aspect of these tractors was brand new. If it didn’t make the operator more comfortable, it made them more productive – or both.

It all started with the frame.

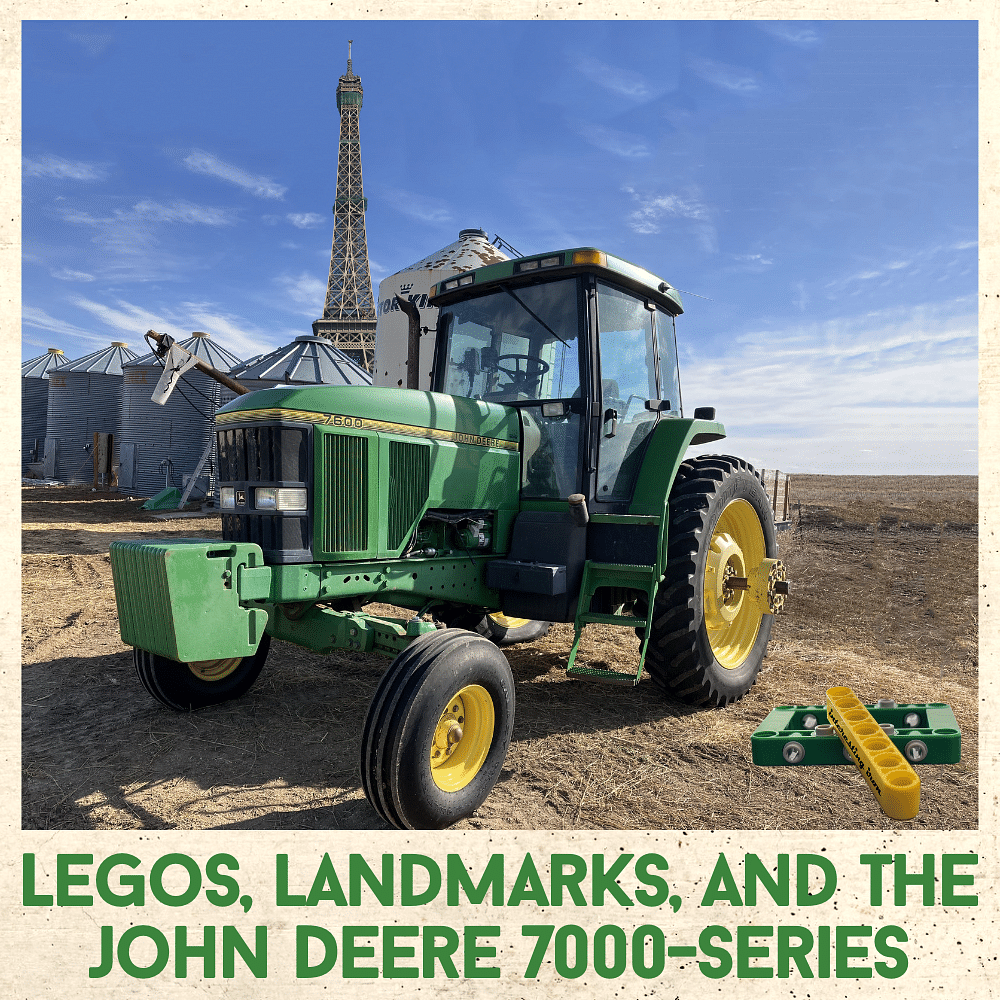

LEGO and landmarks…

The M-Tractor used a main frame (imagine a ladder laid on the ground and you’ll get the idea) where the engine, trans, rear axle, and hitch bolted together and then inside the frame – similar to the way LEGO sets are built. The first prototypes were cast a lot like the old-style stressed member frames – super heavy duty. What they found, though, was that those frames were way too stiff, which caused all sorts of balance and traction issues. To make these tractors work, the frame needed to have a certain amount of flex to it.

The concept of a rigid structure being able to flex a little bit isn’t new. In fact, one of the best examples of it is the Eiffel Tower in Paris. It’s actually pretty lightweight, and its construction allows it to move a few inches if the wind is blowing hard. Still, even though it’s lightweight, it’s very strong and completely rock-solid. The group from Deere incorporated some of these principles into the way they built the M-Tractor’s chassis.

The new frame design offered a number of different advantages. Because the engine wasn’t a stressed member, Deere could use motor mounts to reduce vibration. Less vibration reduced the stress on everything else, from the operator to the driveline and everything in between!

That wasn’t all that was new, though.

TechCenter Cab

The TechCenter cab (I’ve also heard it called the ComfortGard cab) was a completely new design as well. It was roomier than the outgoing SoundGard, with easier entry via wider, adjustable steps and a much bigger door. Inside, every important control was ergonomically laid out so that it was sitting at the operator’s right hand. Cab surfaces and materials were upgraded, as were sound deadening materials. It might not sound like much, but at 72dB, the 7800 was a full 5dB quieter than the 4455. That’s like shutting the door when somebody is using a vacuum cleaner in an adjacent room so you can have a conversation with somebody. It makes a big difference! (It also was the industry leader at the time!)

The Personal Posture seat had been upgraded, too. It was now fully adjustable including 40° of swivel, with lumbar support, and I believe air ride was standard as well. Finally, the dash was completely digital for tractors with a cab. Open-station units shipped with a more weather-resistant setup that used gauges.

Transmissions & Drivelines

Altogether, there were three different transmission options, depending on which model you were looking at. For the two smaller models (7200 & 7400), a 12-speed SyncroPlus was standard, with the 16-speed PowrQuad being the option (it also had a creeper gear available if you wanted it). For the bigger models (7600, 7700, and 7800), the 16-speed PowrQuad was the standard, and the 19-speed PowerShift was the option. Both the PowrQuad and Powershift had shuttle shift built in.

All tractors in the John Deere 7000-Series were available as MFWD or 2WD. I’m not sure which sold better, but if I had to guess, it was probably the MFWD. By this point in time, MFWD had become very popular; lots of farmers would’ve old you that they didn’t have much use for a 2WD anymore!

Engines

There were three engine options in the 7000-Series lineup. The 7200 had a 5.9L turbocharged inline six. Despite being the baby of the family, it made 98 horse on the dyno (which is nowhere near what it’s capable of even in stock form). The 7400 and 7600 both had Deere’s brand new 6.8L turbocharged inline six, producing 107 PTO horse in the 7400 and 111 in the 7600. That engine (and the variations thereof) would go on to become a pretty important part of Deere’s engine lineup down the road as the Power Tech engine family.

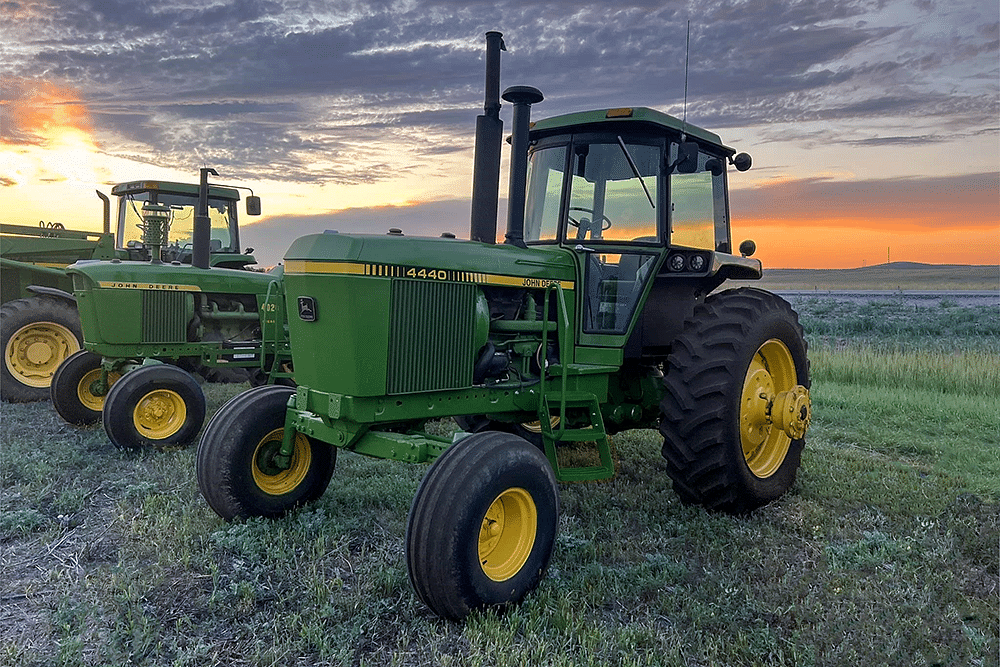

The 7700 and 7800 relied on the tried and true 466 that had been so successful in the SoundGards. The 7700 (the replacement for the 4255) turned a modest 130 horse on the dyno, and the 7800 (the replacement for the 4455) tested at 159.

Sales

While the 7000-Series sold well, they didn’t set the world on fire. I think there were a couple of reasons for that, too. For one, they were all-new, and farmers aren’t early adopters – especially if it looks different than what they’re used to. There wasn’t a ton to be gained by upgrading to an all-new design that hadn’t been proven in the field (again, circling back to the early adopter thing). Furthermore, lots of loyal Deere customers had bought 55-Series SoundGards and they were happy with them!

The big sales numbers would come a few years later when the 7000 TEN-Series launched. By then, farmers wanted more power and capability, and Deere’s 8.1L Power Tech delivered on that promise.

John Deere 7000-Series: The Wrapup…

At the end of the day, while the John Deere 7000-Series wasn’t a commercial success, it definitely wasn’t a flop. It proved a concept – that using a lighter weight modular frame that had some give to it, and building a tractor like a LEGO set – would work. There are thousands of these tractors out there today with some ridiculous hours on them that are still going strong! Furthermore, every tractor company today uses a version of this design for their row crop tractors!

For those reasons, I think these tractors (as well as the 6000-Series) have earned their spot in ag history!

Find a John Deere 7000-Series of your own…

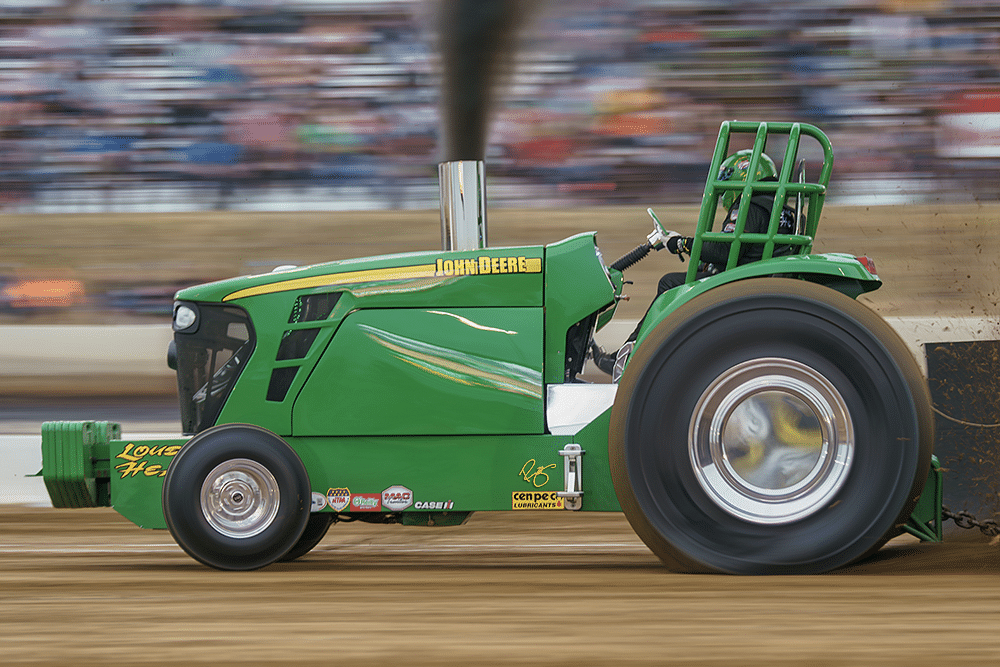

Oh yeah…one more thing. Last weekend’s prostock class at the NTPA Farley Nationals was HUGE. It’s been a long time since I’ve seen 20 pros at an event! Here’s a parting shot from Saturday night of Brandon Simon in his John Deere 7930 called Loud & Heavy! It was a bummer to have to call the show early, but we really needed the rain!

Make it a great week! Don’t step on any LEGOs!