The White Field Boss tractors are generally regarded as some of the toughest tractors to come from the 70s and 80s. They’re stout, overbuilt machines that continue to dot our agricultural landscape even today. As it turns out, they also have an interesting connection to some iconic sports cars, too.

That said, these tractors have a controversial history.

We’ll get into all of that shortly.

First, the details on a pretty nice, low-houred 2-155 Field Boss that’s up for grabs next week in the southwest corner of MI.

Auction Date: May 2, 2023

Auctioneer: DPA Auctions

Format: Online (Bidding is open now)

Location: Dowagiac, MI

TZ Auction Listing

Now, on to the White Farm Equipment story. There’s a lot to unpack here.

Where’d White come from?

Believe it or not…sewing machines. Thomas White founded the White Mfg. Co. in Templeton, MA in 1858. About six years later, the company relocated to Cleveland, and officially incorporated as the White Sewing Machine Company in 1876. For many years, they were a heavy hitter in the sewing machine business.

However, around the turn of the century, Thomas White’s son Rollin spun up a side project – steam engines for automobiles. In 1906, Rollin took the company out on its own as the White Motor Company. They actually had pretty good success, too. Teddy Roosevelt had one for his Secret Service to use, and William Howard Taft had one too. (Side note: The car that Jay Leno was working on when he got burned a few months ago? A 1907 White steamer.)

Through a bunch of twists and turns over the next five decades, White Motor Co. kept building automotive products of one sort or another. Eventually they found their stride in the heavy truck business. They acquired multiple truck brands, and things were going well. By the late 50s, they’d become the one of the largest truck builders on the planet.

White goes farmin’…

Between 1960-1963, White Motor Company acquired Oliver (1960), Cockshutt (1962), and Minneapolis-Moline (1963). By the early 70s, all of these companies had been folded together into White Farm Equipment. Frankly, I don’t think anybody was real happy about it, either. A lot of internal politicking went on, egos got bruised, and business leaders got fired one after another.

(For all of you Oliver, Moline, and Cockshutt die-hard fans out there – you’re right. I condensed a TON of history into four sentences. It’s not that it’s not important – it definitely is. At the end of the day, though, it’d be near impossible to lay it all out in a factual manner. Rather than be disrespectful to one side of the story or another, I figured the easiest way to deal with it is to boil it down to those four sentences.)

At any rate, White Farm Equipment is looking to move forward with a consolidated brand of farm equipment called White. Furthermore, they needed a leader to do it, too.

Now, let’s put a pin in this for a bit. Let’s talk sports cars for a minute, because it ties in.

Movers & Shakers: Bunkie Knudsen & Larry Shinoda

These two guys are pretty much synonymous with sports cars and muscle cars in the the glory days of the American auto industry.

Bunkie Knudsen

Semon “Bunkie” Knudsen was a smart, MIT-educated guy with a tremendous understanding of cars and engines. He started with GM in a Pontiac plant in 1939, and very quickly moved from the bottom up through the ranks. By the mid-fifties, he was managing Detroit Diesel.

In July 1956, he was promoted to VP of GM, and general manager of the Pontiac division. His mission? Ditch Pontiac’s boring, “we’re okay and we’re reliable” image. He was given five years to do it. The first thing he did was to pull the silver streaks off the hood and trunk of the 1957 Chieftain cars, sending a very clear message that Pontiac was no longer going to be a boring car. He ushered in an era of high performance with the wide-track designs of the late fifties, and followed those up with bona fide high performance cars. He even put Pontiac back on the drag strip and with a little help from Smokey Yunick, back into stock car racing!

The results were pretty undeniable, too. The brand that was once on the chopping block rocketed to number three in sales! Bunkie was promoted to Chevrolet’s GM in 1961, and the presidency was in sight.

Except that it wasn’t. GM’s top brass passed him over for President, hiring Ed Cole in late 1967.

That’s when Bunkie started to look for the door.

As it turned out, the door Bunkie found had a blue oval on it. In February of 1968, he accepted Henry Ford II’s offer to run the show at Ford. When he did, he took Larry Shinoda with him.

Larry Shinoda

Larry Shinoda became one of the automotive design legends of our time, but his life had a pretty rough start. Born in Los Angeles in 1930, he and his family were rounded up under FDR’s executive order during WWII due to their Japanese heritage. They were sent to Manzanar, an internment camp in central California, when he was 12, and he spent several years there. He made the best of it, but it wasn’t pleasant.

Larry got into the So-Cal hot rod culture in the late 40s when he was in high school. He was a heck of a builder, and an even better racer, setting Bonneville records as well as picking off a win at the first NHRA Nationals in 1954!

At any rate, he put himself through school and was accepted into the Art Center of Design in L.A. He knew exactly what he wanted to do. He wanted to design cars. Ultimately, that’s what got him kicked out, too. He saw zero value in sketching bowls of fruit, so he didn’t go to class.

It was probably the best thing that ever happened to him.

Shortly thereafter, he nailed an interview with Ford, and they moved him to Detroit. A couple years and a job or two later, he went to work for Harley Earl as a senior designer at GM. Larry’s dynamic sense of style coupled with his racing background had landed him a dream job, designing Chevrolet’s concept Corvettes and racecars!

While at Chevrolet, he became good friends and colleagues with Bunkie Knudsen. When Bunkie left Chevrolet, Larry wasn’t far behind.

Back in the saddle…

By mid-1968, Bunkie & Larry were once again shaking things up – this time, at Ford. The Mustang had done well, but it was developing a reputation as more of a cute car, rather than a performance car. The 1969 version was a little bigger than previous models, and it didn’t have the look that Ford wanted. Bunkie turned Larry loose on it, with a goal of a much racier, limited production model that would qualify them to go Trans-Am racing. When he was finished with the styling, he’d created the Boss 302 – arguably one of the most beautiful Mustangs ever built.

Bunkie & Larry also played a role in the Torino and a hotted-up version of the Cougar (the Eliminator), as well as a few longer-term changes for the 1971 model years. Sadly, their time at Ford would be pretty short-lived. There were some interpersonal “issues” between Bunkie & Lee Iacocca (it’s pretty clear in Lee’s autobiography that he never liked the guy), and Bunkie got the short end of that deal on September 11, 1969. Larry left a few weeks later.

Now…back to farm equipment.

I know that was a long buildup, but honestly, it was warranted. These two guys built some amazing things together during their time at GM and Ford.

After the dust settled, Bunkie & Larry went into business for themselves. They formed a company called Rectrans. What’d they build?

Motorhomes.

Yep, they went from building the most beautiful, iconic sports cars in America, to building motorhomes. Personally, I think they were hideous. Do a Google image search if you’re not squeamish. I don’t have the heart to put a photo of one in here.

At any rate, the folks at White Farm Equipment were watching all of this happen, and they saw an opportunity. They needed leadership with a proven track record, and these guys had it. After some negotiating, White bought Rectrans as part of a deal to get Bunkie on the payroll as President, and Larry as the VP of Design. It was a little different for both of them (especially Larry), but they got right to work.

The first project on the list? Come up with a name to rally around.

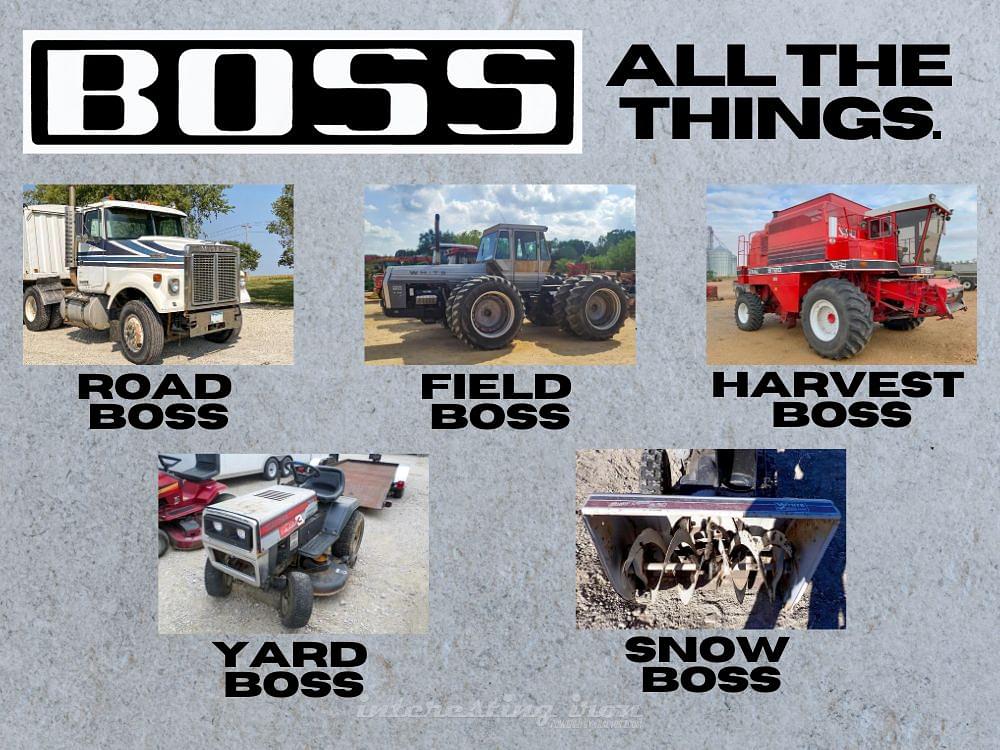

Project #1: “Boss” all the things.

White’s new leadership team decided to lean in to the Boss name. It had worked for Ford with the Mustangs, so why not?

They went all in, too; I’m pretty sure everything with a White badge on it from about 1972 through into the mid 80s was a Boss of some sort – even snowblowers! (I almost wonder if that wasn’t a real subtle poke in the chest to Lee Iacocca and Ford.)

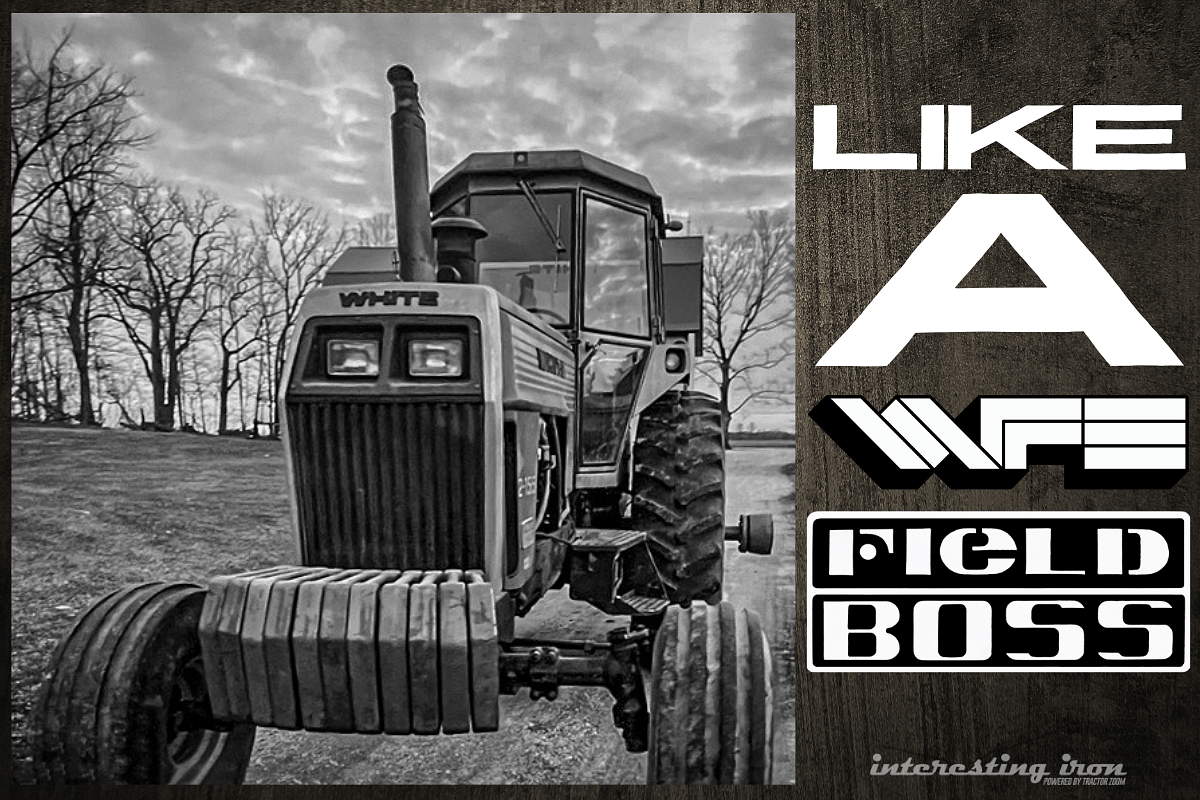

The Field Boss

As VP of Design, Larry went to work styling the Field Boss line, which would be released in 1975, starting with the 4-150. The tractors were sleek and very modern, and featured quiet, comfortable cabs too. The new White tractors made a strong statement; we’re here, and we’re built for business. If the performance could match the looks, the company was sure they’d have a winner.

Performance

With the exception of just a few models and applications, the performance was pretty solid. Where it made sense, White basically re-skinned several smaller Oliver tractors with new sheet metal and/or a few tweaks here and there. The 2-70 was a 1655, the 2-85 was a 1755 with a Perkins 354, and the 2-105 was a 1955 with a turbocharged Perkins 354. Lots of parts interchanged.

The bigger tractors (for the purposes of this article, I’m referring to the 2-135 and 2-155) followed a similar methodology. However, they got a heavier, beefier frame than just about any rowcrop that had ever rolled out of Charles City, and a nearly indestructible planetary rear end. They still used the familiar over/under 3×6 transmission and the turbocharged 478 Hercules from the Oliver 2150 (which was a stout engine if there ever was one). In the field, these tractors were heavier than any other tractor in their class, and they were built like a brick outhouse. They made tons of torque and plenty of power, which was just the way White wanted it.

Sales

For the most part, the new designs were well-received. The farmers who had the most heartburn over the new machines were the loyal Oliver and Minneapolis-Moline owners. A lot of them felt betrayed by the company, and ended up looking elsewhere. Some still have a love/hate relationship with these tractors today.

The 2-155 and 2-135 tractors were far and away the most popular of the Field Boss lineup, and White moved a lot of ’em. In fact, I believe that those two tractors were in production longer than any other White rowcrop (1976-87). There were a few changes here and there, but not many. The most major change was moving to a new cab for the Series III tractors in late 1982. The new cab was more comfortable and quiet than ever, and it’s definitely the one to get if you can find one.

Now, let’s talk about the 2-155 Field Boss you can buy next week. It’s a pretty good one!

The one you can buy on auction…

It’s a 1978 model on 20.8s with duals, a full rack of front weights, and a broken tach. However, while that’s a reasonable description, I wondered what else I could find out about the tractor. So I called Jon, the fella who owns it. Turns out that we hit it off, and ended up talking for about 45 minutes the other night! Nice guy, and more than willing to answer questions about it.

Jon bought this Field Boss 30-35 years ago at a consignment auction near Decatur, IN with about 1200 hours on it. It was stripped when he bought it – no weights on the rack and no duals. Not long after he bought it, he tracked down the original owner and talked him into selling the weights and duals. It’s been on the farm ever since. For a while, it was the big horse, and it was mainly a plow tractor. Jon was a fruit and veggie grower, so it got a workout with a 6-18 every spring.

Issues

As far as problems go, it’s only ever had two major issues – the tach and the over-under. The tach died somewhere between 26-2700 hours; Jon thought it was a sending unit or a sensor or something. He never was able to track it down. He’s kept track of the hours since it died, and estimates that it’s got about 3500 original hours on it.

Many years ago, the over/under locked up one Saturday in the spring. They didn’t have the time to deal with it, as they needed to be in the field, so they put it in the shed until the winter when they could fix it. Jon called his local Deere dealer at home on Sunday afternoon and bought a 4455 over the phone, and the next morning it was sitting in the driveway. The following winter, he split the Field Boss and fixed it, and it was ready to go again the following spring.

“Toughest machine I’ve ever owned…”

When I asked him how it performed, he said, “Ryan, that tractor is probably the toughest machine I’ve ever owned. It absolutely manhandled that 6-18 plow. I never turned it up, and I never put it on a dyno, but it’s gotta be making 175 or more. It blows plenty of black smoke!” Honestly, that wouldn’t surprise me at all. I’ve heard and read multiple stories about owners who put stock 2-155s on the dyno and saw higher numbers than that!

“Overall,” he said, “It’s been a very reliable, trouble-free tractor. The only reason I’m selling it is because I’ve retired, and I don’t need it anymore.”

Field-ready?

Jon told me that for the past 10-15 years, the tractor has had a pretty easy life. It’s seen some occasional use during spring tillage, but overall, very minimal use. For the last two years, it’s been parked, as he retired about two years ago. To be field-ready, it’ll need new batteries and a fluid flush. Other than that, though, it should be ready to go. Jon borrowed batteries when he got it out for photos, and he said it fired it right up.

Overall, the tractor is in great shape. The interior is clean and tight, save for a tear in the seat. The AC blows nice and cold, too.

What’s it worth?

Overall, the tractor is in great shape. The interior is in much better condition than the average. It runs and drives very well, and the tires are reasonably good, too. Those all play in the tractor’s favor. It’s not a Series 3, but it’s a very nice example of a Silver Stripe!

The things that play against it are few, but potentially significant. Let’s face it, nobody loves reading “tach doesn’t work” in an auction listing. That could turn off a few bidders. I believe that the hours noted (3500) are correct because I talked to Jon for close to an hour. Some will skip over it just based on that alone.

The other thing that could play against the tractor is the engine. Yes, the 478 is tough as nails, but when if/when it needs an overhaul (somewhere around 6000 hours, if history repeats itself), it can get a little spendy. I’ve always been told that Maibach Tractor in Creston, OH is the place to go for parts.

Still, at the end of the day, I think this is probably a $10-11K tractor. (Maybe a little more if the right people happen to read this article!)

Wrapping up…

The love/hate relationship that some Oliver and Moline fans have with White as a company is tough. On one hand, I totally get it. These two companies built great products, and it wouldn’t be hard to make the argument that they got swallowed up by a company that didn’t place proper value on that heritage.

On the other side of that coin, I don’t think it’s entirely fair to pin the demise of the other two brands solely on guys like Bunkie Knudsen and Larry Shinoda, either. I mean, the tractors that Oliver and Moline had in production were long in the tooth. Let’s face it; they looked old, and the market didn’t want that. They wanted fresh, modern styling, and that’s what the Field Boss delivered. (Yes, I know Oliver had the “Corporate Tractor” in development; I’m glad to see that there’s a team up in Floyd County working on putting one back together!)

Truth be told, I don’t think there’s any one or two people or events that put the nails in the coffin for Oliver, Moline, and Cockshutt. It was a long line of poor management decisions, workplace politics, and circumstances beyond anybody’s control that all stacked up together to put the company in the place it was in.

At the end of the day, one thing is for sure. The Field Boss tractors that rolled out of Charles City were built by the same hands that built Oliver and Moline tractors. Same dedication to quality, and the same dedication to the farmer.

That’s something to be proud of, y’know?